More than Lending: Building Communities Through Affordable Housing

Jump to project profiles

“A big pull for me to come to Capital Impact was its commitment to affordable housing. Little did I know that I’d be starting off in a dead sprint,” said Diane Borradaile, Capital Impact’s Chief Lending Officer.

In March 2018, on literally Borradaile’s first day on the job, she learned that Capital Impact had been named by Washington D.C.’s Mayor to serve as a fund manager for the city’s first ever Housing Preservation Fund.

“When you walk in the door and realize the Mayor of a major city entrusts you with a multi-million dollar housing fund and an ambitious goal to deploy that money within a year, it is quite an honor…but also, quite frankly, a little terrifying given that Capital Impact was still relatively new to working on housing issues in the District,” remembers Borradaile.

Diane Borradaile, Capital Impact’s Chief Lending Officer, began her career working for New York City’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development. The mission focus of the agency is something that has stuck with her to this day.flected Jane Garcia, the CEO of La Clínica de La Raza.

And just as Borradaile was wrapping her head around this opportunity, Capital Impact learned that it would be part of the Chan Zuckerberg $500 million “Partnership for the Bay’s Future” initiative to support affordable housing development in the San Francisco Bay Area. Like D.C., this was also a region where Capital Impact was still fairly new to addressing affordable housing.

Needless to say those first few months were hectic, but exciting, and they reaffirmed her decision to join the organization.

“I’ve had a chance to catch my breath just a bit, but I’m happy to say we are still running at top speed to address this critically important issue.”

When Mission and Opportunity Align

Borradaile’s very first job was working for New York City’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development. The mission focus of the agency is something that has stuck with her to this day.

“For too long, people across this country—especially in communities of color—have been shut out from the ability to access safe and affordable housing as a result of systemic and racist policies based on skin color. These historical barriers have created lasting impacts when it comes to health, education and the ability to create wealth. Activating a housing strategy based on the principles of equity, opportunity and inclusion is critical to breaking down these barriers to success,” explains Borradaile.

Borradaile is also quick to remind everyone that Capital Impact’s focus on affordable housing is really a return to its roots. That’s because the company was formed as a spin-off from a cooperative bank in the early 1980s with a mission to finance “all forms of consumer, worker and producer cooperatives—thus, contributing to the economic development of low- and moderate-income communities.” And many of those were housing cooperatives.

For too long, people across this country—especially in communities of color—have been shut out from the ability to access safe and affordable housing as a result of systemic and racist policies based on skin color. Activating a housing strategy based on the principles of equity, opportunity and inclusion is critical.

– Diane Borradaile, Capital Impact Partners, Chief Lending Officer

“So it’s not a total surprise that Capital Impact works in this space,” says Borradaile. “It makes sense…especially now with heightened attention to issues of gentrification and income inequality.”

Not only do these opportunities to engage with key partners in Washington, D.C. and the Bay Area help Capital Impact address these issues, but they also dovetail with the organization’s five-year strategic plan. Launched in 2016, this strategy prioritizes a focus in five key geographic regions, including Detroit and the Great Lakes region, the Bay Area, Los Angeles, Sacramento and San Diego in California, the greater Washington, D.C. region, central Texas (including Austin, Dallas, Fort Worth, Houston and San Antonio areas) and New York City and its surrounding areas.

“By having staff members on the ground and working shoulder-to-shoulder with community partners who live and work in these neighborhoods,” added Borradaile, “we are better able to tailor our products and services to respond to the needs of those markets and the issues they face.”

“By having staff members on the ground and working shoulder-to-shoulder with community partners who live and work in these neighborhoods, we are better able to tailor our products and services to respond to the needs of those markets and the issues they face,” notes Borradaile.eflected Jane Garcia, the CEO of La Clínica de La Raza.

And while this focus has helped, it was clear no “one-size-fits-all” strategy was going to work.

“The number of years we’ve spent working on housing in Detroit has provided us with some good lessons learned,” said Ian Wiesner, Capital Impact’s Detroit based head of Business Development. “However, expanding across these diverse geographies requires a tailored, on-the-ground approach to implementation. That’s because historical context, local markets, incentives, stakeholders, tenant organizations and the legal landscape vary substantially across regions.”

Other layers Capital Impact must address are the various housing types they support, ranging from senior and cooperative housing to mixed-use (projects that include both residential and retail components). They must also focus on how to utilize different types of financing for larger and more complicated transactions.

In each of these places, Capital Impact is finding community partners to work with—those with boots on the ground who know the obstacles and opportunities and can best help Capital Impact leverage its assets.

Casamira Apartments, Detroit: “And before you knew it, we were in over our heads."

“So you drive down the block, and you go, ‘Wow, is this really Detroit?,’” Johanan, Co-founder of social services organization Central Detroit Christian (CDC), laughs. “It’s just so beautiful. It looks like a picture out of a novel or a movie. And then you come upon this building. It’s historic and it’s Art Deco. And so I was very excited despite the fact that it had had a fire, was dilapidated and there were only four tenants in there and we hadn’t figured out how to get them out. But it was one of those buildings that was easy to fall in love with. And before you knew it, we were in over our heads.”

“When Lisa Johanon, Co-founder of Central Detroit Christian, first laid eyes on the Casamira apartment building in Detroit’s North End, it was love at first sight: “It’s just so beautiful. It looks like a picture out of a novel or a movie. And then you come upon this building. It’s historic and it’s Art Deco.”

Lisa founded Central Detroit Christian as an outgrowth of her work in youth development. Working and living in the neighborhood which historically contained the city’s poorest zip code, she soon realized that one of the most critical factors in young peoples’ lives was housing stability.

The issue came into stark relief when a young boy from the neighborhood approached Johanon, asking her to help his family who were living with rats in their rental house. Johanon marshalled the resources to secure the home for the family and soon began shifting the focus of her social service work to home repair and rehabilitation. Johanon and a group of Detroit pastors created the Central Detroit Christian Community Development Corporation in 1993 after recognizing the need for unified action to create social impact for neighborhoods in their city.

“We’ve got to invest in properties, and we’ve got to rehab and we’ve got to build,” she says. “We’ve got to do all of this because this is a major issue with folks who need affordable housing.”

“This really is an up-and-coming neighborhood. It was a great neighborhood before the decline of Detroit. We need to be honoring that. And so we knew this needed to be a mixed-income building,” says Johanon.

Before laying eyes on Casamira, CDC had only worked on affordable housing. But Johanon knew that the Casamira neighborhood required a different approach.

“This really is an up-and-coming neighborhood. It was a great neighborhood before the decline of Detroit. We need to be honoring that. And so we knew this needed to be a mixed-income building,” says Johanon. “We as an organization are very committed to affordable housing. It couldn’t just be market rate, which is what the neighborhood is in general. But we knew there had to be that component to it for us to be true to our mission as a nonprofit organization.”

The property, which was vacant and had fire damage, was donated to CDC in 2013 out of probate court. Although CDC had developed some small housing projects before, the four-story, 42,200-square-foot property was by far the largest project the organization had ever taken on. And Johanon knew that despite the exquisite beauty of the historic structure, which was built in 1925, it would be a tough slog to get it ready for tenants.

Securing financing to rehabilitate the property was a massive challenge for CDC. Historic tax credits were delayed and initial investor agreements fizzled as Johanon tried to find a capital stack that would work in a highly uncertain market.

“Capital Impact Partners was always there. They really helped us through some of the issues that we were having with other lenders. They knew everybody in the city or state who could help us and were a great guide to us getting this project completed.”

Hear more from Lisa as she talks about the challenges of getting the Casimara project off the ground in this video.

Taking a Risk on Detroit

“In 2016, Detroit was still risky business in many respects,” says Johanon. “Detroit was still really shaky. We didn’t know if the building would appraise. So being as conscientious as we could with the finances was very, very important.”

But as Johanon worked to build the right capital stack, real estate values and construction costs in North End—as in other gentrifying neighborhoods across Detroit—were on the rise.

“It took a good three years to put the financing together,” says Johanon. “And all the while, the construction dollars kept going up.”

By the time the project was completed, CDC had brought in seven layers of financing and incentives to invest $10.4 million in the building. The result created 29 new market-rate and 15 affordable apartments available to the community. Capital Impact Partners came in with a $3.8 million construction loan. But for Johanon, it was as much Capital Impact’s guidance as its financing that made the project ultimately happen.

“Capital Impact Partners was always there. They really helped us through some of the issues that we were having with other lenders. They knew everybody in the city or state who could help us and were a great guide to us getting this project completed.”

Hear more from Lisa as she talks about the challenges of getting the Casimara project off the ground in this video.

“Capital Impact Partner’s role was just that they were always there,” says Johanon. “They really helped us through some of the issues that we were having with other lenders. Ian Wiesner (a Business Development Manager at Capital Impact Partners) knew everybody in the city or state who could help us. And so, he was a great guide to us getting this project completed.”

Serving as Lender…and a Partner

For Wiesner, it’s all in a day’s work; he is accustomed to making the extra effort to help worthy projects that preserve affordability and protect Detroit’s history that otherwise might not happen cross the finish line.

“As a mission-driven lender, we pride ourselves on going the extra mile to see that impactful projects get done,” says Wiesner. “In this case, we worked to combine city, state and federal incentives to support this important mixed-income project that included both market-rate and income-restricted housing. In addition, we helped lead the closing process. We worked through the construction issues inherent in historic renovation in Detroit as well as structured a transaction that satisfied the various requirements of the different sources of subsidy.”

Ultimately for Capital Impact, the project is about much more than the deal. It’s about equity and housing justice.

By the time the project was completed, CDC had brought in seven layers of financing and incentives to invest $10.4 million in the building. The result created 29 new market-rate and 15 affordable apartments available to the community, which is critical for a city where housing inequality is stark.

Addressing The Issue of Housing Inequality

Housing inequality in Detroit is stark. Detroit’s median household income is $27,838—only half that of the state of Michigan—and it has double the state’s poverty rate. According to a 2019 report by the Michigan League for Public Policy, nearly half of Detroiters are housing cost-burdened, meaning the median cost of housing exceeds 30 percent of a household annual income. Among renters, that number is as high as 49 percent. Detroiters are also plagued by tax foreclosures and high water and electricity rates.

Fewer than 22,000 units are classified as affordable by AMI benchmarks in the city. This is happening during a period of growth and development in the city that has not been seen in decades. However, that growth has occurred almost exclusively in the city’s Downtown, Midtown and New Center areas, pushing out existing residents—many of whom are people of color. At the same time, there’s been little or no housing development in Detroit’s neighborhoods.

In 2017, the city of Detroit adopted an Inclusionary Zoning Ordinance to help low-income Detroiters benefit from the new development boom. The ordinance requires developers accepting $500,000 or more in subsidies from the city to price 20 percent of units for households making up to 80 percent of Area Median Income (AMI). However, two-thirds of cost-burdened Detroiters make $20,000 or less per year—far below that AMI benchmark.

Capital Impact Partner’s role was just that they were always there. They really helped us through some of the issues that we were having with other lenders.

– Lisa Johanon, CEO, La Clínica de La Raza

As Capital Impact Partners began working in Detroit in 2011, the organization realized that it had a role to play in addressing housing insecurity in the city. They saw a need to go beyond lending and act as a partner to Detroit developers intent on building the type of inclusive, affordable, mixed-use housing that helps create jobs and access to services and amenities. It was a strategy created to help reverse those systemic policies of disinvestment and redlining that create barriers for communities of color from achieving the types of opportunities that start with stable housing.

According to Capital Impact Partner’s Chief Lending Officer Diane Borradaile, the company’s experiences in Detroit led it to embrace this new focus.

“Affordable housing is really about building inclusive neighborhoods,” says Borradaile. “It became clear to us that housing has the potential to really change a community and people’s lives. And Capital Impact wanted to support development that didn’t lead to the types of displacement seen across the city.”

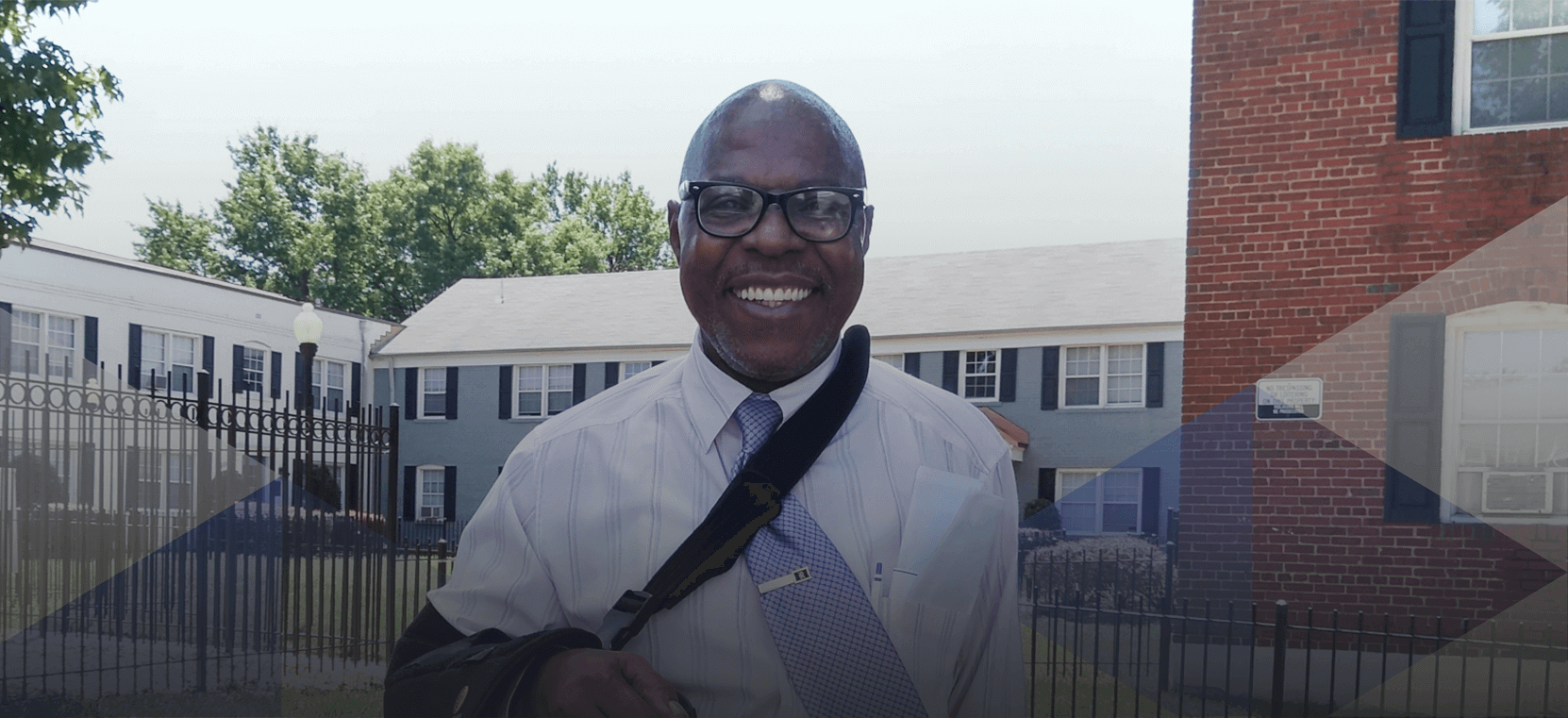

Today, Casamira is entirely occupied. Property manager Calvin Kilgore says he takes pleasure in waking up every morning to help serve people by giving them an opportunity to save and build a life through solid, affordable housing. Most days, he says, he can’t stop smiling.

From Dream to Neighborhood Anchor

Today, the Casamira units are entirely occupied. Property manager Calvin Kilgore says he takes pleasure in waking up every morning to help serve people by giving them an opportunity to save and build a life through solid, affordable housing. Most days, he says, he can’t stop smiling.

“Throughout the city we’ve seen people are paying rent without the ability to save money, working just to live,” says Kilgore. “We want people to be able to build and establish something. That’s where we come in, offering affordable units.”

And as rents continue to rise in New Center and beyond, Casamira and similar properties, provide lower-income, longtime residents with an option to remain in their neighborhoods.

“We were the new kids on the block,” says Johanon. “This was a project with multiple layers of financing; it was way more complicated than anything we’d done before. And Capital Impact’s guidance steered us through.”

Capital Impacts’ years of experience in Detroit helped create the lessons learned for the organization to tackle affordable housing in other cities with notable housing affordability challenges like Washington, D.C.

Worthington Woods, Washington, D.C.: "An anchor of stability in a prominent location"

Soon after Jamison settled into his new place, his neighborhood became a hotspot for redevelopment and gentrification. The building he had just moved out of was converted to high-end condos, and the existing tenants were forced out. Soon, the owners of his new building also wanted to cash in.

“Residents feared that a new owner was going to get rid of these apartments—redo and gentrify them like they do all around the city, making them unaffordable,” Jamison recalls.

“Residents feared that a new owner was going to get rid of these apartments—redo and gentrify them like they do all around the city, making them unaffordable,” Worthington Woods tenant Ronnie Jamison recalls.

That’s when Jamison and his neighbors, with the help of the Latino Economic Development Center, joined forces to form the Worthington Woods Tenants Association to exercise their rights under the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA).

TOPA was passed by the D.C. Council in 1980 to help protect low-income renters in gentrifying neighborhoods by giving them the right of first refusal to purchase their rental properties. Capital Impact Partners’ strategy in D.C. is to leverage TOPA projects that are also close to basic needs—such as jobs, transit and other services—to help build up inclusive neighborhoods.

“Once we formed the tenants’ organization, what we did is just like a job. We had the right to select the developer who we felt would be most beneficial for us,” says Jamison.

The tenants’ organization signed their TOPA rights over to Montgomery Housing Partnership (MHP), a nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving affordable housing opportunities. This project was the organization’s first in the District. At 14.5 acres, Worthington Woods is one of the largest holdings in private hands in D.C.

An Ambitious Plan Meets a Pressure Filled Timeline

That started the clock on an ambitious plan to secure $40 million in financing to buy and rehabilitate the property. Under TOPA, MHP had just months to put a deal together or risk the rights to sell the property reverting to the original property owner.

“The Worthington Woods purchase is important to MHP because it enables us to broaden our impact, expand our efforts to preserve affordable housing and provide residents services into the District of Columbia,” says MHP President Robert A. Goldman. “By preserving a substantial quantity of affordable housing, this purchase will enable residents to remain in the neighborhood where many of them have resided for years. Worthington Woods provides an anchor of stability that is in a prominent location and is of significant size.”

Housing in D.C. is rapidly becoming unaffordable for all but the most affluent. Partnerships between Capital Impact and mission-driven developers like Montgomery Housing Partnership are working to prevent that by preserving critically needed affordable housing using D.C.’s TOPA law.

With pressure building because of deadlines imposed under TOPA and contractual agreements for financing, MHP began working on a backup plan with Capital Impact Partners for bridge financing.

The timing was fortuitous. Prior to being approached by MHP, Capital Impact had been named by D.C.’s Department of Housing and Community Development (DHCD) to help manage its recently created Housing Preservation Fund (HPF). The Fund was created as part of a larger strategy by D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser to preserve long-term affordability and avoid displacement of residents and families in areas of the city that were increasingly targeted for development.

Capital Impact leveraged a portion of its grant from DHCD to provide MHP with a $6.1 million loan that was ultimately part of a larger $40 million financing deal that included Sandy Spring Bank.

Housing in D.C. is rapidly becoming unaffordable for all but the most affluent. A 2018 report showed that 62 percent of housing units in the District are unaffordable for a household earning the average median family income. And despite robust housing policies, including TOPA, an Inclusionary Zoning Program, the Housing Production Trust Fund, DHCD and others, the problem remains. According to a 2018 study conducted by the D.C. Policy Center, the main drivers of unaffordable housing in the District include a combination of unbalanced supply and demand, competition for larger units by affluent singles and couples without kids, legacy racism and restrictive zoning, among others.

Washington, D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser speaks at event celebrating the Worthington Woods financing, a project that helped meet the city’s target of preserving 1000 affordable homes.

“The preservation of Worthington Woods will ensure that 394 homes stay affordable, helping the District of Columbia reach its target of preserving 1,000 homes in 2019,” says Goldman. “Another important aspect is that MHP has agreed to a covenant of perpetual affordability, which provides peace of mind to residents and gives the District a lasting foundation of affordable housing stock upon which to build.”

Capital Impact’s Involvement Made All the Difference

According to Artie Harris, MHP’s Vice President of Real Estate, Capital Impact’s involvement made all the difference.

“It would have restricted MHP’s ability to do additional projects until we got the permanent financing,” said Harris. “With the Capital Impact funding, now we can proceed to do other deals, and it gives us a stake in the District.”

Ultimately, MHP’s purchase of Worthington Woods, in addition to preserving 394 units of affordable housing, includes a portion of revenue from cash flow and fees annually going back into the tenants’ organization. The funds will support community development programs and services like senior activities and after school programs as determined by the tenants’ association.

The difference, just in the little time since MHP has acquired this property and we put in the tenants’ association, is great; we’re seeing changes already.

– Ronnie Jamison, Worthington Woods Resident

For Jamison, it’s been a blessing to not only remain in his neighborhood, but also to benefit from upgrades, including installation of individual centralized HVAC units and planned construction of a clubhouse for community activities and resident programs.

“The difference, just in the little time since MHP has acquired this property and we put in the tenants’ association, is great; we’re seeing changes already,” says Jamison.

Worthington Woods was part of a larger success story in Washington, D.C. In just its first year of managing the HPF, Capital Impact leveraged its grant from the city to deploy more than $28 million in financing to support five projects and help protect 860 affordable homes. This directly supported an estimated 1,960 residents—1,948 of whom have low-to-moderate incomes.

Based on that success, the District chose Capital Impact to help manage the fund in 2020.

Depot Community Apartments, Hayward, CA: System Changing Financing to Address the Bay Area's Affordability Crisis

Largely a problem of too little supply for the booming demand, housing costs in the region have continued to rise, pricing out all but the region’s top earners. This issue has forced lower-income workers to commute farther and has contributed to the growth of the homeless population.

Proposed policies to address the crisis generally center on the need to build more affordable housing within a complicated and competitive real estate environment. Capital impact is leveraging its resources and finding new partners to become a part of the solution.

A key part of that strategy is Capital Impact’s role in the Bay’s Future Fund (BFF). The Fund is part of a larger $500 million effort launched by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative along with the San Francisco Foundation, Ford Foundation, Local Initiatives Support Corporation and others. The Partnership is working to advance meaningful change to address critical housing needs, prevent displacement and support racial and economic inclusion across the Bay Area.

Capital Impact’s first project financed under the Bay’s Future Fund will focus on formerly homeless persons with serious mental illness or other disabilities. Amenities will include opportunities for engagement in community rooms and outdoor space for recreation. A supportive services plan will include vocational and employment assistance as well as primary health and dental referrals.

In December, Capital Impact closed on its first affordable housing loan in the region. The Depot Community Apartments project includes a $2.66 million acquisition loan from Capital Impact as part of a $5.6 million loan from CSH (Corporation for Supportive Housing), financed through the BFF. The loan will help affordable housing developers purchase a three-acre parcel in the City of Hayward.

The co-owners include Allied Housing, Inc., a nonprofit whose mission is to provide affordable housing linked to supportive services for low-income individuals and families, and Abode Services, Inc., a nonprofit with a mission to end local homelessness. Abode offers housing programs linked to supportive services for homeless families, single adults and youth.

The proposed project will focus on formerly homeless persons with serious mental illness or other disabilities. Amenities will include opportunities for engagement in community rooms and outdoor space for recreation. A supportive services plan will include vocational and employment assistance as well as primary health and dental referrals.

Our task is not only to develop this permanent supportive housing project, but to build an inclusive community, and to work in close collaboration with our stakeholders to maintain ongoing stewardship of that community – one that will strive to serve all individuals, every day,” said Macy Leung, the Depot Community Apartments project manager for Allied Housing. “We appreciate the support of Capital Impact Partners through the Bay’s Future Fund, and the commitment of our community partners to address the region’s critical affordable housing needs.

Our task is not only to develop this permanent supportive housing project, but to build an inclusive community, and to work in close collaboration with our stakeholders to maintain ongoing stewardship of that community.

– Macy Leung, Depot Community Apartments Project Manager, Allied Housing

“Capital Impact’s financing will have a strong impact in the community,” says Capital Impact Senior Loan Advisor Andrew King. “It will facilitate further predevelopment for a project that will help increase the supply of new housing to address the Bay Area’s homelessness crisis.”

Borradaile says Capital Impact is well situated to connect with the Bay Area community, having operated an office in Oakland since the 1990s with a substantial lending history in the region and state.

“And with the BFF as a tool, Capital Impact is well positioned to do some financing that will be system changing for the affordable housing crisis.”

“What makes Capital Impact unique is that we are not just a lender,” she says. “We strive to also be a partner. We rely on the local knowledge of our community partners and combine that with our technical and financial expertise to do projects that may not happen otherwise.”

LEARN MORE ABOUT OUR WORK

Harnessing Co-ops to Expand Housing in Texas

By partnering with NASCO properties in Austin, TX, we are able to harness the power of cooperatives as a way to expand affordable housing options in the city.

Looking for Affordable Housing Financing?

At Capital Impact we pride ourselves on ensuring that good projects that create social impact get the financing they need.

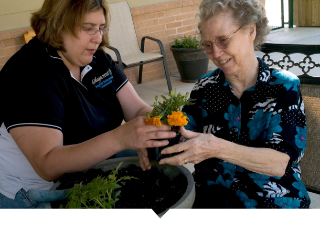

Better Housing for Older Generations

Affordable housing enriched with social services fills more than just a housing gap for older adults on fixed incomes.